|

After extensive research on 135 novels/short stories located in our 1880s Children Fiction corpora and selected novels from our 1880s Adult Fiction corpora (see our corpora), we noticed recurring themes and research questions, too many to address individually.

Each and every text of the 1880s Children Fiction corpora, downloaded as a plain text through Project Gutenburg, was analyzed by our text analysis team. Research included looking up novel summaries and author backgrounds and running them through different software, ranging from Antconc to Lexos to Voyant Tools. We found Voyant Tools to provide the most easy-to-understand information regarding relationships among chosen words. However, Antconc did give us insight into how the words were being associated, especially in regard to who boys were portrayed differently than girls and in regard to the word choice of particular authors. The text-analysis research folder in our shared Google Drive contains around 150 research documents providing summaries, text-analysis visualizations, and notes on individual novels. One document, called Categories, arranges authors according to male/female main characters. (E.g. George W. Peck [male] is author of Peck's Bad Boy and His Pa, a novel on Henry Peck [male]; Emma Leslie [female] is author of Kate's Ordeal, a novel obviously featuring Kate [female].) The Categories catalog shows that out of 29 female authors and 105 male authors, the men overwhelmingly wrote about male characters (with effectively zero of them writing solely about female characters), and the women wrote mostly about female characters. Subsequently, we were curious to see how this affected the way the stories were written, and how gender roles were defined in children's literature.

We focused our research on gender and its appearance in different works. We began with Jo's Boys by Louisa May Alcott, because we were all vaguely familiar with the storyline. Our findings eventually served as the basis for our research question: how do male and female authors portray boys and girls differently? Are girls more likely to be presented in a positive light when they're written about by female authors? How well do male authors write female characters?

Jo's Boys uses the word "boys" slightly less frequently than the word "girls," which was surprising because the book is primarily about boys. We also noticed that the word "don't" co-occurs with "girls," while "won't" intersects with "boys" more frequently, possibly revealing something about how the author believes boys and girls should behave ("don't" generally conveys a command, while "won't" usually conveys resistance).

We also noticed that Jo's Boys contains a lot of words with positive sentiment ("like," "good," "dear," "great," "happy," "love," "better"), possibly because of the female author.

Other examples include Robert Louis Stevenson's Kidnapped and Susan Coolidge's A Little Country Girl. Kidnapped is set around the time of the Appin Murder and tells the story of David Balfour making his way in the world after his parent's death. It is widely known as a boys' novel.

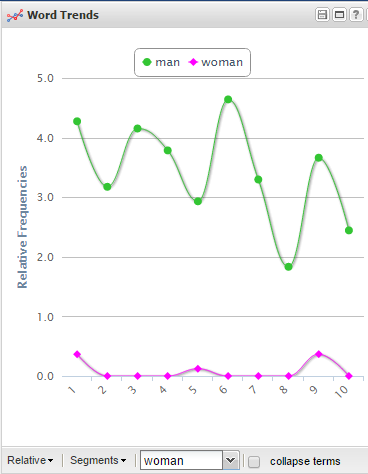

Voyant Tools shows the frequency of "man" in Kidnapped. The word appears 280 times. The first visualization represents the profile of "man" in the novel's most frequent vocabulary. Clearly, "man" is most frequent. The second visualization compares "man" and "woman." Our relevant research questions: why did most adventure novels include a high frequency of male characters but no mention of female ones; why are male authors more inclined towards writing about boys and action, ... etc. Voyant Tools shows the frequency of "man" in Kidnapped. The word appears 280 times. The first visualization represents the profile of "man" in the novel's most frequent vocabulary. Clearly, "man" is most frequent. The second visualization compares "man" and "woman." Our relevant research questions: why did most adventure novels include a high frequency of male characters but no mention of female ones; why are male authors more inclined towards writing about boys and action, ... etc.

The next visualization concerns Susan Coolidge's A Little Country Girl, a story about Candace, an orphan, who teaches other girls her age moral lessons about honesty and kindness.

The most frequent words were "girls," "mamma," "mrs.," "mother," "miss," and "girl"--all female terms. This visualization shows the relative frequencies of the specified terms. Both "boys" and "boy" are rarely mentioned. Similarly, other texts written by female authors showed identical analyses. A research question that occurs to us: how do gender roles and moral lessons correlate?

We also analyzed a few selections from the 1880s adult fiction corpus. One was Marooned by William Russell, which we looked at in Voyant tools:

In this word cloud, the words “man,” “men,” and “miss” all appear frequently (as indicated by the size of the words in the graphic.) The title of this novel indicates that the tale is about sailors marooned on an island. The use of mostly male terms leads us to believe that the male author was aiming primarily for a male audience. The single female term “miss” may represent a lone female character who adds interest to the plot line. Other terms such as “sea,” “deck” and “island” lead us to trust our original hypothesis: that this novel is about adventures aboard a ship and its misadventures. There are also many more large or complex words in the word cloud, such as “digitized” and “broadside,” than in most of the books intended for children.

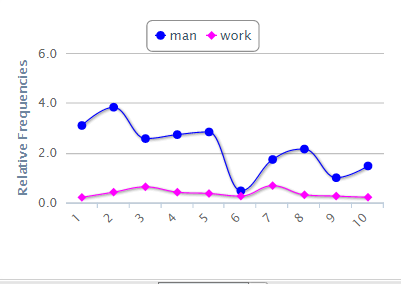

These frequency comparison charts show that the term “man” appears much more often than “miss.” But both are similarly associated with the word “work.” This is a pleasant surprise. Both the women and the men seem to receive an equal share of the credit for effort, although one singular woman with that much “work” and an untold number of men with the same amount may hint at an inequality of work in the novel.

We analyzed a few works of adult fiction to compare writers and their habits. Sarah Tytler's Beauty and the Beast and Henry James' A Portrait of a Lady served as good examples.

We can see here that the gender of characters is about equal. Both "lady" and "sir" and "woman" and "man" are up on the frequency chart. Henry James' novel is similar.

Another pattern we found in the children's literature was not only that the majority of the novels were focused on boy adventure, but also that these boys were more often than not portrayed as heroes of the story. This was always the case if the story dealt with war, but even when it did not there was always one boy who did something heroic throughout the text. For example, Oliver Optic's All Adrift uses the words "wildest" and "wandering" to describe the boy protagonist. This reinforces the idea that boys were seen as the more adventurous sex.

On the other hand, women are not described as wild, or strong. Instead, they are characterized in tender words that makes one think of them as fragile. Or, again, they are described in words concerning women's duties. In Elsie's New Relations by Martha Finley, words correlating with women include "sex," "foolish," "family," and "alone." Those words do not appear in the case of men in the story. This is interesting, given that the work was written by a female author. We would expect her to use empowering words for her sex; but our analysis did not show that to be the case.

Although most stories written by female authors center on a female character, there are exceptions. In Five Little Peppers and How They Grew by Margaret Sidney, we found that the frequency of the words "women" and "girls" was not as high as that of "men." Even though the story is about five children, the most talked about among them are the male children. Did the author do this because she expected the majority of her audience to be males, because it was the norm that boys are written about most?

Despite the location of frequency, it's there. Adult fiction writers incorporated many and more characters into the story, while children's fiction writers focused on one certain character and gender. So then we have to ask: Does having too many characters detract from the meaning and focus that authors expected children to take away from their novels? The Victorian Web argues that in children's literature, "boys will be boys and girls should be girls." During the Victorian era, boys were associated with racy adventure stories, while girls were charmed by domesticity and home, religion, lady-like behaviors, etc. And that is exactly what we found. Based on this, we can ask if female authors who went against the norm and wrote about adventurous girls found it hard to maintain their audience?.

Class text analysis team: Jennifer Chang, Ginny Chung, Eve Kopecky, and Sinead Leon.

|

Comments (0)

You don't have permission to comment on this page.